by William Steele (revised by Mary Schwarz and Jean Bonhotal, 2017)

There's nothing worse than a pile of dead fish. Except maybe a pile of the leftover parts of dead fish: heads, tails, internal organs and all that. Disposing of this waste can be a problem for anyone who cleans and processes fish, from big commercial food processors to small sport-fishing operations.

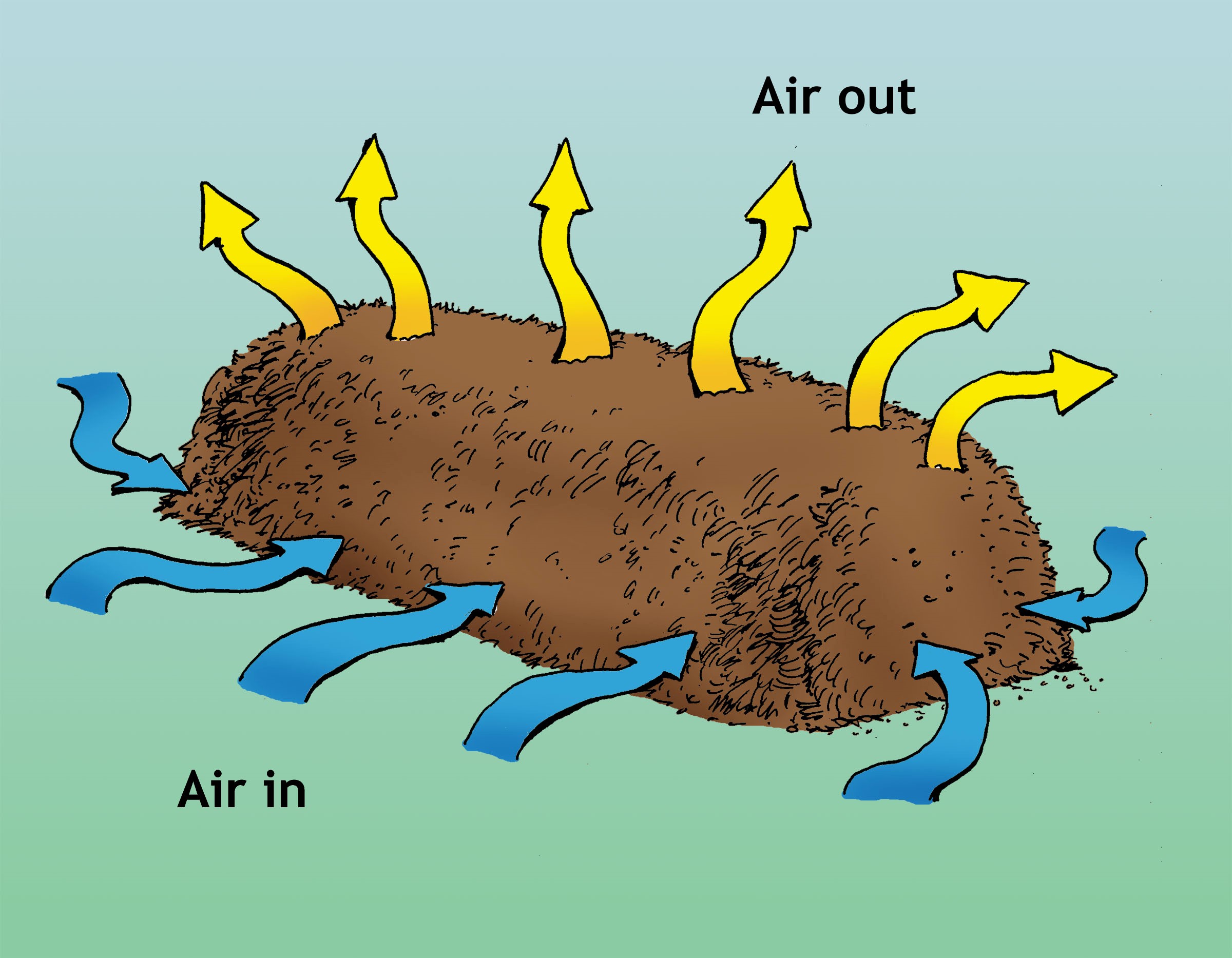

Composting may well be the answer; static pile/windrow composting may be the most efficient waste-stabilizing technology available to the processor. The fish/shells are layered into a windrow of course carbon. The carbon absorbs the moisture and neutralizes the odor and the layering allows air to circulate to the microbes that are doing the work. Build a windrow or pile greater than 6 x 6 x- as long as there is space. The pile will heat due to microbial metabolism, heat will rise and cool oxygen rich air will be pulled into the pile. If good coarse carbon is used, the air will naturally circulate and the pile will not need to be turned. This is an essential benefit when wo rking with putrescible, odiferous material.

Mortality windrow with course carbon.

In composting, the high nitrogen, wet flesh and shell are mixed with course carbonaceous, dry materials such as shavings, wood chips, leaves, branches or bark. Microorganisms in the pile feed on the waste and over a period of several months convert it into rich humus. In the process, the microorganisms generate a great deal of heat which reduces pathogens in the product, eliminating odor, disease organisms and destroying weed seeds.

The resultant product can be used or sold as a soil amendment or soil enhancer. Composting is no more difficult than brewing beer or baking bread, two other processes that take advantage of a different kind of microorganism. Anyone can do it, but as with brewing or baking, no one should expect a perfect process or a saleable product the first time around.

It was and sometimes is common practice to dump fish waste back into the lake or ocean. The trouble is that dumping it all in one place can overload the ecosystem, so dumping is banned to protect our water bodies, animal and human health. That can leave fish processing plants with a lot of waste on their hands. Some have found other markets, grinding up the waste to make cat food or converting it to liquid fertilizer by a process called hydrolysis, but much of it is still going into landfills. In Alaska, where fish-related enterprises are the third largest employer, three billion pounds of waste are generated annually, several fish processors have taken advantage of the large amount of woodchips available from the local timber industry to operate large-scale fish/shellfish composting operations.

Many small processors have implemented composting as well. For example, some sport-fishing operations on Lake Ontario are using this technology to compost the waste from fish cleaning stations in lake and stream-side piles. The eastern shore of Lake Ontario manages about 1,000,000 pounds of fish parts annually. Fish-waste composting is a little trickier than the backyard variety, but is similar to farm mortality, roadkill and butcher waste composting.

Troubleshooting Table

Symptoms |

Problems |

Recommendations |

Pile fails to reach temperature |

Material is dense. Not enough air circulation.

Pile too small.

Frozen carcass place in pile. |

Rebuild pile with more chunky carbon. To heat, pile needs to be greater than 4’x4’x4’. May need to wait until warmer weather to reach temperature. |

Insects and other animals attracted to pile. |

Flesh/shell waste not covered well. Leachate puddling on pad surface. |

Cover residuals well with carbon. Pad should have 1-2% slope and holes should be filled to avoid standing water. |

Flesh/shell waste uncovered. |

May have insufficient cover. |

Use plenty of carbon cover material. |

Standing water/surface ponding. |

Inadequate slope.

Improper windrow/pile alignment.

Depressions in high traffic areas. |

Establish 1-2% slope with proper grading. Improve drainage, add an absorbent like woodchips. Run windrows/piles down slope, not across. Fill and grade. |

Odors |

Ponded water.

Insufficient cover.

Anaerobic conditions. |

Regrade the site to make sure there is no standing water. Make sure piles are covered with at least 2 feet of wood chips. Build piles so that they are not too wide or too dense so that air flow can keep the piles aerobic. DO NOT turn or disturb piles for 3-4 months (depending on the size/amount of waste). Turning can release odors, especially early in the process. |

For information on composting butcher waste, see CWMI’s mortality composting resources at http://cwmi.css.cornell.edu/mortality.htm.

Additional mortality composting resources (access at: http://cwmi.css.cornell.edu/mortality.htm): Natural Rendering: Composting Poultry Mortality - 12pg fact sheet, 6-min video and illustrated poster.

Natural Rendering: Composting Livestock Mortality and Butcher Waste: 12 pg fact sheet, 20 min video and 3 illustrated posters.

This article appeared in the Cornell Chronicle (08/11/94).

More Tales of Weird and Unusual Composting

|

Composting |

Engineering |

in Schools |

|

Cornell Waste Management Institute ©1996

Department of Crop and Soil Sciences

Bradfield Hall, Cornell University

Ithaca, NY 14853

607-255-1187

cwmi@cornell.edu